I have been trying to stockpile some posts for while I am away, and had bookmarked a couple of the koan stories from the Shinji Shobogenzo after reading the Shobogenzo fascicles that Dogen included them in – you could think of the the three hundred koans that he compiled (supposedly overnight right as he was about to return to Japan), now called the Shinji Shobogenzo, as a reference encyclopedia, which he dipped into in order to illustrate a point he was wanting to make in his main writings or his talks.

Despite having two translations on hand, the Nishijima version and the Daido Loori version, I found myself hesitating. Whatever spark had initially inspired me to note the stories did not stand up to scrutiny later.

Although I appreciate the centuries-long history of koans, and their role in helping students break out of stuckness and typical conceptual thinking (I first typed that as thunking, which might be a good neologism for stuck thinking), I couldn’t see the value in posting either story for you all to ponder over your morning coffee, or whenever it is that you read these posts.

Perhaps this is indicative of how far I have strayed from traditional Zen teaching; perhaps it is a necessary and invetiable questioning of how we can bring the traditional teaching to bear in the present age.

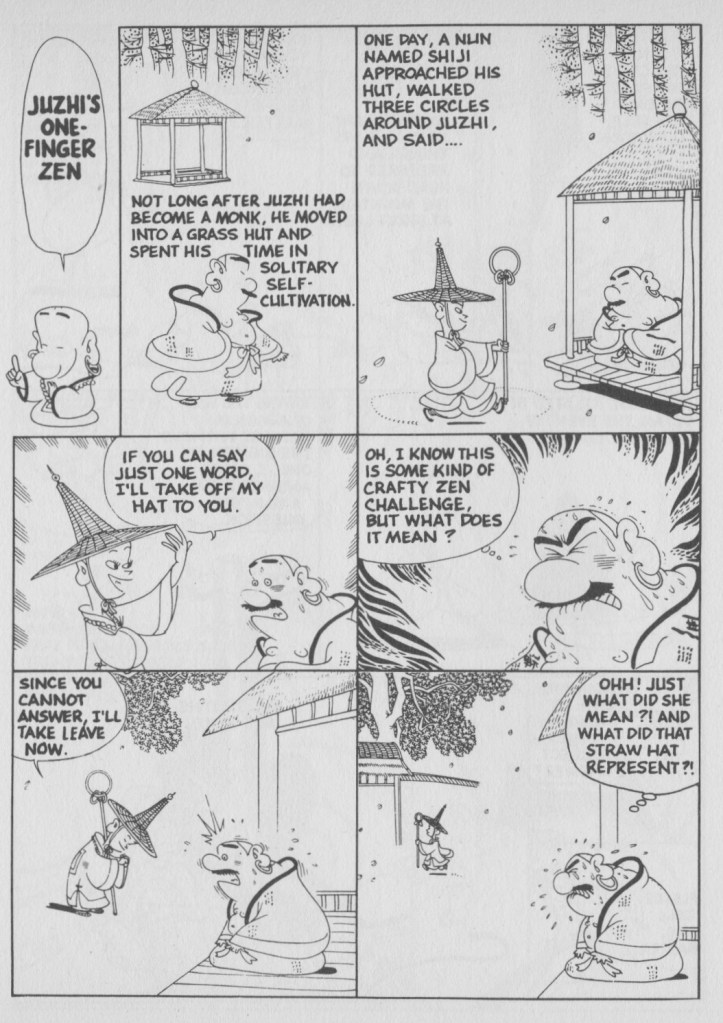

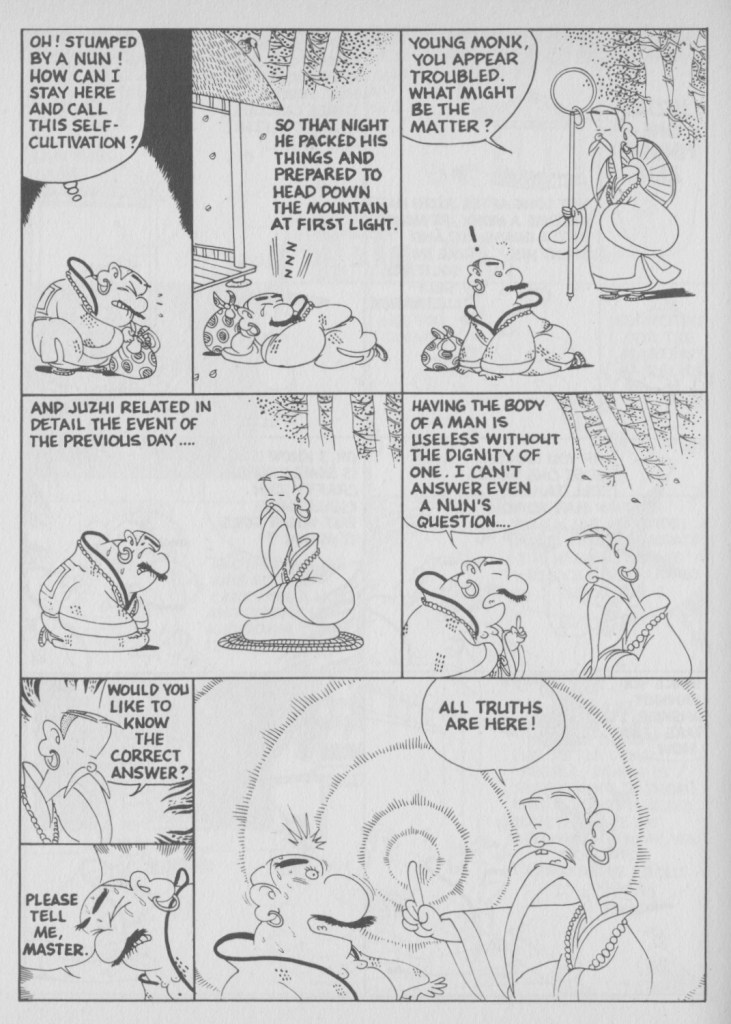

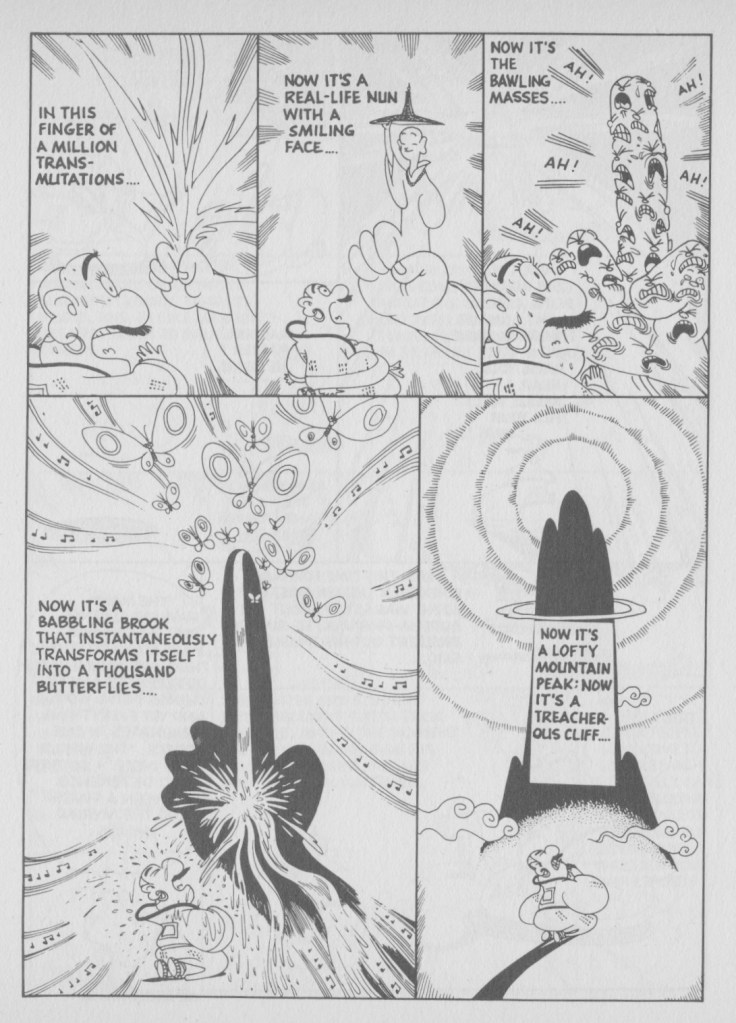

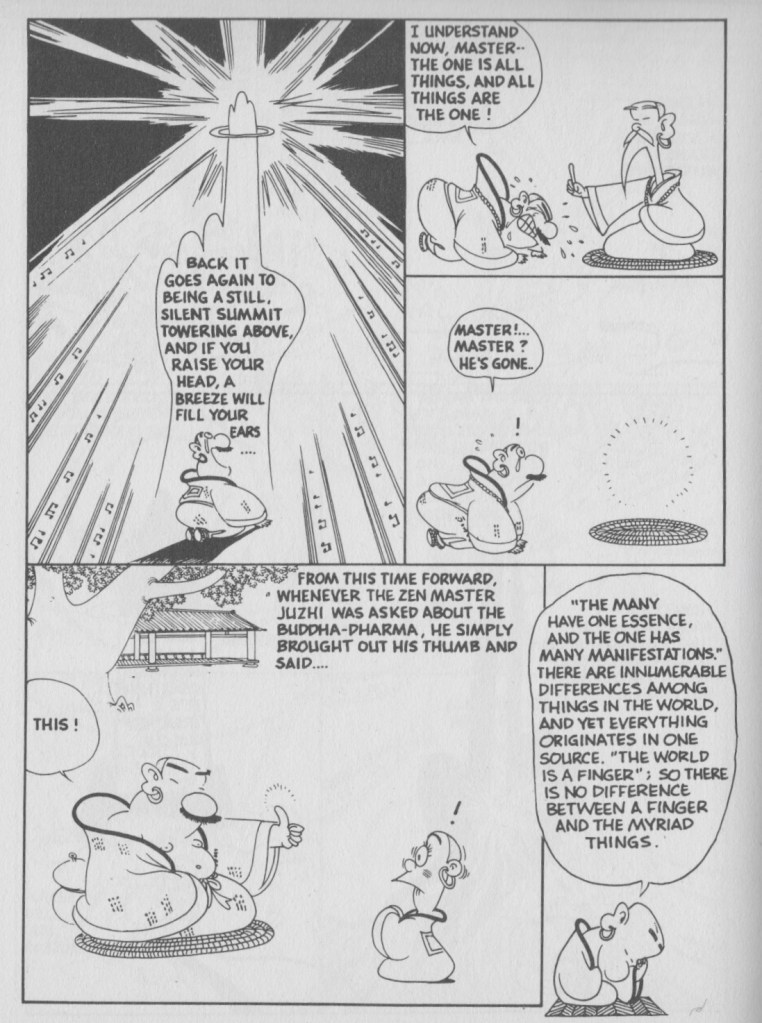

And, in last week’s Monday Suzuki Roshi class, we looked at a talk from the first sesshin at Tassajara, in which Suzuki Roshi introduced three stories as a way to illuminate form and emptiness. We tackled only the first one during the class, Gutei’s One Finger. We had some discussion as to the brutality of the act of cutting off a disciple’s finger – as a way of shocking him out of the idea that he knew what he was doing – and whether we can just read the violence, as with other cases like Huike cutting off his own arm, or Nansen cutting a cat in two, as metaphorical devices. Suzuki Roshi was certainly making a point to his students not to be stuck on the idea of a training period, or a sesshin, even though these were new and momentous things for everybody involved, but to understand that practice continued moment after moment, whether we could label it (as a form) or not.

I brought up my first exposure to this story, which definitely brings home the vividness of the story, as other examples did all those years ago. Here it is in full:

(I am aware I don’t make many posts like this; perhaps if I had a little more time and silence in my current life, I would do better – if this is something you would like to see more of, please let me know, and I will try)

Leave a reply to shundo Cancel reply